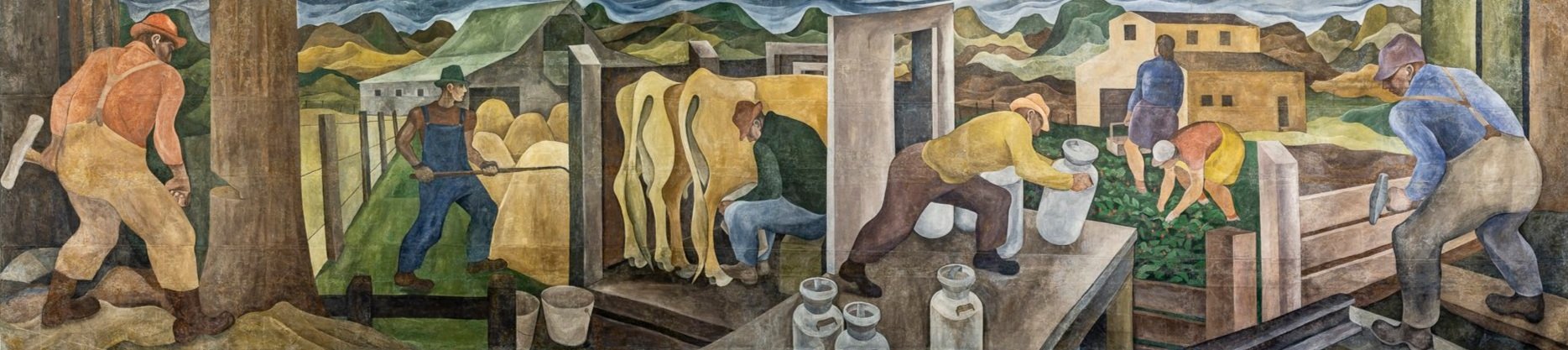

William Cumming’s Mural

All photography on this page is credited to Tim Mickleburgh

Lost and Found: Mural of Skagit County Agriculture

by Northwest Master William Cumming

In 1941, a 24-year-old art critic, photographer, and fledgling artist named William Cumming produced a remarkable work for the National Youth Administration: a 28-by-7-foot mural on linen sailcloth, destined for Burlington High School’s new “farm shop.” The scenes depicted farm life in the Skagit Valley in the style known as social-realism: felling timber, baling hay, milking cows, loading a milk wagon, picking berries, and building railroads.

Cumming, on his way to becoming one of Seattle’s most important and beloved artists, never again painted an agricultural scene. And once the nation recovered from World War II, much of the publicly funded art of the Depression, like his Farm Shop mural (formally known as “Mural of Skagit County Agriculture 1941”) were quietly retired. A teacher at the school, Edward Breckenridge, folded it up, took it home, and stored it in his barn along with paraphernalia from the Skagit County Junior Livestock Show.

To his unsuspecting family, it looked like an old utility tarp. “My nieces used it to measure their long-jumps,” according to Edward’s son, Tony Breckenridge. In the summer of 2014, Tony dragged it out into the rain, and was about to take it to the dump when he noticed a colorful image, “a cow’s butt,” on the inside of one of the creases.

What came next is a chain of unusually happy coincidences. Tony Breckenridge called Brian Adams at the Skagit Parks Department, who hung the mural at the Skagit County Fair; a reporter for the Skagit Herald, Shannen Kuest, put a photo of the mural in the paper; a Skagit resident and patron of the arts, Sharene Elander (who passed away in early 2017), sent a copy to her longtime friend and art dealer John Braseth in Seattle; and Braseth immediately recognized the long-lost Farm Shop mural from 1941 and further confirmed his identification by authenticating the scuffed-up Cumming signature.

Several years ago, fire ravaged the Breckenridge family house and barn. If Tony hadn’t spotted that cow’s posterior and turned the tarp over to the county, the piece would have been lost forever. Instead, it’s now in the permanent collection of the Museum of Northwest Art in La Conner and is valued in the high six figures. But decades of life in boxes in barns, not to mention occasional use as a long-jump landing pad, have taken their toll. The mural has undergone restoration and is ready to claim its reputation as a major piece of Northwest history.

- Ronald Holden, Seattle Historian